- Wet Tropics Management

- Legislative framework

- Management partnerships

- Sustainable Tourism Plan

- Threats to the Area

- Research and a Learning Landscape

- How can I help?

Everything! Rocks are the foundations of the landscape and the origin of the soil. They even affect the weather. For example, the the coastal mountains of the Wet Tropics trap rain-laden clouds from the moist ocean breezes. Over time, rain erodes the rocks at an imperceptible rate creating the lofty crags, ridges, valleys, gorges and spectacular waterfalls which form the dramatic landscape. Rock fragments accumulate on lower slopes to form a variety of soils which in turn support a range of forest types (see regional ecosystems).

Soils in the Wet Tropics are predominantly derived from granites and rhyolites, and metamorphic sedimentary rocks. They vary from thin, stony, leached and infertile ‘lithosols’ of some ridgetops to the deep, red, rich and fertile basalt derived soils of the Atherton Tableland and the alluvial soils of the coastal lowland plains which can be over 60 metres deep.

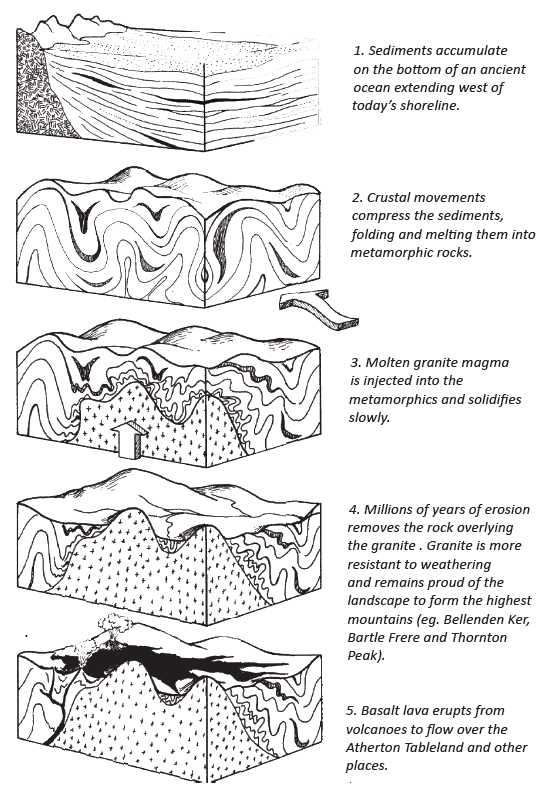

Below is a brief history of the geology of the Wet Tropics and its three main types of rock forms—metamorphics, granites and volcanics.

About 260 million years ago a mass of molten rock (magma) solidified slowly deep below the Earth’s surface, forming a body of hard granite (see left). Over time, as the surrounding softer land surfaces were eroded away, this granite became exposed. Weathering removed loosened material along weak fractures extending downward through the rock. More resistant rock remained as large rectangular blocks. The rock is actually a light grey colour. The black colour we see is due to a film of microscopic blue-green algae growing on the surface. The grey colour of the rock can be seen where the boulders have recently broken. Cold rain falling on hot rocks sometimes causes this to happen in a loud, explosive fashion.

Lake Eacham and Lake Barrine are explosion craters, known as a maars, created when rising lava came into contact with ground water. The resulting steam caused a violent explosion as it burst through the rocks on the surface producing a crater. Little volcanic material is produced by this sort of explosion. It forms a low ridge around the crater. The craters of Lakes Eacham and Lake Barrine may have been formed as recently as 10,000 years ago—their explosive creation is remembered in the stories of local Aboriginal people. After the explosion, water collected in the crater, forming today's lakes which are up to 65 metres deep. The weight of this water has caused the surrounding rocks to sag, creating a much larger crater and lake.

Lake Eacham and Lake Barrine are explosion craters, known as a maars, created when rising lava came into contact with ground water. The resulting steam caused a violent explosion as it burst through the rocks on the surface producing a crater. Little volcanic material is produced by this sort of explosion. It forms a low ridge around the crater. The craters of Lakes Eacham and Lake Barrine may have been formed as recently as 10,000 years ago—their explosive creation is remembered in the stories of local Aboriginal people. After the explosion, water collected in the crater, forming today's lakes which are up to 65 metres deep. The weight of this water has caused the surrounding rocks to sag, creating a much larger crater and lake.

Wherever the water is able to slowly drain out of an explosion crater a swamp forms, such as Bromfield Swamp. Some maars—Lake Euramo, Bromfield Swamp and Lynch’s Crater—are up to 200,000 years old. They are excellent historical resource for looking at the pollen record.

Mount Hypipamee crater is thought to have been created by a massive gas explosion. As the gas rose suddenly through a crack in the Earth’s surface, pressure on it was reduced and the gas expanded. The massive explosion as it burst through to the surface created a deep cylindrical hole or pipe through the granite. The walls are 55m high and the small lake which has formed in the bottom is another 87m deep. The explosion hurled boulders and rocks into the air, but little volcanic material was produced. This feature is known as a diatreme. Mount Hypipamee is the only known example of this in north Queensland.

Mount Quincan, and the Seven Sisters, near Yungaburra, are volcanic cones created by explosive eruptions. As vents opened, volcanic materials were hurled into the air, falling to build up cones around them. These were composed of compacted volcanic ash and scoria—light-weight volcanic rocks with gas bubble cavities.